Rocketship X-M

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

| Rocketship X-M | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Kurt Neumann |

| Screenplay by | Kurt Neumann Orville H. Hampton (additional dialogue) Dalton Trumbo (Martian sequence, uncredited) |

| Produced by | Kurt Neumann Murray Lerner (executive) Robert L. Lippert (presenter) |

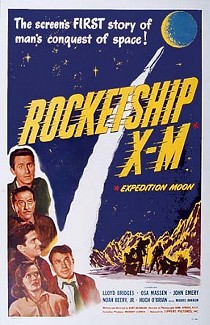

| Starring | Lloyd Bridges Osa Massen John Emery Noah Beery Jr. Hugh O'Brian Morris Ankrum |

| Cinematography | Karl Struss |

| Edited by | Harry Gerstad |

| Music by | Ferde Grofé |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Lippert Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 78 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Budget | $94,000[1] |

| Box office | $650,000[1] |

Rocketship X-M (a.k.a. Expedition Moon and originally Rocketship Expedition Moon) is a 1950 American black-and-white science fiction film from Lippert Pictures, the first outer space adventure of the post-World War II era. The film was produced and directed by Kurt Neumann and stars Lloyd Bridges, Osa Massen, John Emery, Noah Beery Jr., Hugh O'Brian, and Morris Ankrum.

Rocketship X-M tells the story of a Moon expedition gone awry. Through a series of unforeseen events, the expedition's crew find themselves on the infamous red planet, Mars. During their time on the planet they go on to discover the remnants of a Martian civilization destroyed long ago by atomic war and now reverted to barbarism.[2]

Plot

[edit]Four men and a woman blast into outer space from the White Sands Proving Ground aboard the RX-M (Rocketship Expedition-Moon) on humanity's first expedition to the Moon. Halfway there, after surviving their jettisoned and runaway first stage and a meteoroid storm, their engines suddenly quit. Recalculating fuel ratios and swapping around their multiple, different fuels corrects the problem, supposedly allowing continuing to the Moon. When the engines are reignited, the RX-M careens out of control on a rapid heading beyond the Moon. The increased acceleration causes the crew pass out. Reviving days later, they quickly discover that they have traveled some 50,000,000 miles; the RX-M is now just 50,000 miles away from Mars. Dr. Karl Eckstrom is forced to "pause and observe respectfully while something infinitely greater assumes control".

[ At this point the film changes from black and white to tinted red ]

The RX-M safely passes through the Martian atmosphere and lands. The next morning the crew, clad in aviation oxygen masks due to the low oxygen levels, begin exploring the desolate surface. They come across physical evidence of a now dead advanced Martian civilization: a partially buried-in-the-sand, stylized, Art Deco (or Tiki culture) like metal face sculpture and in the distance Moderne architecture-like ruins. Their Geiger counter registers dangerous radiation levels, keeping them well away. These dangerous levels make it clear that there was once an atomic war on Mars in the distant past.

Finding cave refuge, the crew notice in the distance the primitive human descendants of that civilization emerging from behind boulders and creeping toward them. Amazed, Dr. Eckstrom comments "From Atomic Age to Stone Age". Soon after leaving, two of the explorers encounter a dark-haired woman who has lost her footing and rolled down a hill toward them; she is blind, with thick, milky cataracts on both eyes. She screams upon hearing their oxygen mask-distorted voices. The radiation burned tribesmen attack, throwing large rocks and stone axes. Armed with only a revolver and a bolt-action rifle, the explorers defend themselves, purposely missing the primitives. Major Corrigan is killed by a large rock thrown by the primitives. Moments later, Dr. Eckstrom is killed by a stone axe. Navigator Chamberlain is badly injured by a large thrown rock. Colonel Graham, Dr. Van Horn, and Chamberlain finally make their way back to the ship.

[ At this point the film changes from tinted red to black and white ]

As the RX-M nears Earth, the three survivors (Graham, Van Horn, with the unconscious Chamberlain) calculate that they have no fuel to make a landing. Col. Graham contacts their base and reports their dire status to Dr. Fleming, who listens intently and wordlessly over headphones. Col. Graham's report is not heard, but Fleming's subtle reactions tells of the crew's odyssey, their discovery of a once advanced civilization destroyed long ago by atomic war, and of the crew fatalities at the hands of Martian descendants reverted to barbarism.

Col. Graham and Dr. Van Horn embrace as the RX-M begins its uncontrolled descent, consoling one another in the moments left to them. Through a porthole, they bravely watch their rapid descent into the wilds of Nova Scotia. The press is later informed by a shaken Dr. Fleming that the entire crew has perished. When they ask if the mission was a failure, he confidently responds with conviction, stating that all theories about crewed spaceflight and exploration have now been proven. He continues, underscoring the point that a dire warning has been received from the crew that could very well mean the salvation of humanity, "A new spaceship, the RX-M-2, begins construction tomorrow". The pioneering exploration continues.

Cast

[edit]- Lloyd Bridges as Col. Floyd Graham (Pilot)

- Osa Massen as Dr. Lisa Van Horn (Ph.D. in Chemistry and developer of the unique "mon-atomic hydrogen" fuels which power RX-M)

- John Emery as Dr. Karl Eckstrom (Physicist and RX-M designer)

- Noah Beery, Jr. as Maj. William Corrigan (Flight engineer)

- Hugh O'Brian as Harry Chamberlain (Astronomer and navigator)

- Morris Ankrum as Dr. Ralph Fleming (Project Director)

- Sherry Moreland as blind Martian woman

- Judd Holdren as Reporter (Uncredited)

- Stuart Holmes as Reporter (Uncredited)

- Bert Stevens as Reporter (Uncredited)

- Cosmo Sardo as Reporter (Uncredited)

- Barry Norton as Reporter (Uncredited)

Film score

[edit]The evocative soundtrack was written by American composer Ferde Grofé (composer of Grand Canyon Suite), who used a theremin in portions of the score. This was the first use of an electronic musical instrument in a science fiction film. The theremin would later become strongly identified with the genre in the years to come.[3] During the film's post-production, Grofé's score was conducted by film and TV composer/arranger Albert Glasser. Later on, the soundtrack would have its first release in 1977 on LP (runtime 37:16) from Starlog Records (SR-1000). The album contains a bonus track not used in the film.[4]

The CD version of the soundtrack was released in 2012 and was produced by Monstrous Movie Music (MMM-1965) in an edition limited to 1000 copies. The CD's 16-page illustrated booklet contains extensive information about the film score, which includes pages from Grofé's original hand-written score and photos related to the film production.

- Main Title (1:21)

- Good Luck (1:53)

- Stand by to Turn (0:50)

- The Motors Conk Out (2:55)

- Palomar Observatory (1:11)

- Floyd Whispers (1:57)

- Floyd and Lisa at Window (2:56)

- We See Mars (2:06)

- The Landing on Mars (3:17)

- The Ruins (3:10)

- I Saw the Martians (1:02)

- The Atomic Age to Stone Age/The Chase (4:59)

- The Tanks Are Empty (3:37)

- The Crash (3:22)

- End Title (0:59)

- Bonus Track: Noodling on the Theremin (1:35)

Production

[edit]Because production issues had delayed the release of George Pal's high-profile Destination Moon, Rocketship X-M was quickly shot in just 18 days on a $94,000 budget; it was then rushed into theaters 25 days before the Pal film, while taking full advantage of Destination Moon's high-profile national publicity.[3]

Given the film's minimal special effects budget and limited shooting days, the surface of Mars was much easier to simulate using remote Southern California locations than creating the airless and cratered surface of the Moon.[3] The location where the crew exits the spacecraft and begins to explore is Zabriskie Point in Death Valley National Park.

The film's original 1950 theatrical release prints had all Mars scenes tinted a pinkish-sepia color.[3] All other scenes are in black-and-white.

The RX-M's design was taken from rocket illustrations that appeared in an article in the January 17, 1949 issue of Life magazine.[4] The interior structure of the spaceship's larger second stage is shown as having a long ladder that the crew must climb; it runs "up" through the RX-M's fuel compartment, which has on all sides a series of narrow fuel tanks filled with various propulsion chemicals. By selecting and mixing them together in various proportions, different levels of thrust are attainable from the RX-M's engines. The crew ladder ends at a round pressure hatch in the middle of a bulkhead floor that leads to the crew's upper living and control compartment.[3]

Instruments and technical equipment were supplied by Allied Aircraft Company of North Hollywood.[2]

Historical and factual accuracy

[edit]The five Mars explorers wear U.S. military surplus clothing, including overalls and aviator's leather jackets.[2] It has been noted in other film reviews that the explorers are wearing gas masks, but gas masks would include goggles to protect the eyes. Due to the thin Martian atmosphere, the explorers are actually wearing military "Oxygen Breathing Apparatuses" (OBA) like those used by military firefighters.[4]

Various scientific curiosities and errors are seen during the film:

With less than 15 minutes to go until launch, the RX-M's crew are still in the midst of a leisurely press conference being held at a base building. From its launch pad, the RX-M blasts straight up, and once it leaves the Earth's atmosphere, the ship makes a hard 90-degree turn to place the RX-M into Earth orbit. Its speed at an altitude of 360 miles is stated to be 3,400 mph (1.5 km/s); in fact at that height orbital velocity is 18,783 mph (8.397 km/s) (though escape velocity is approximately correctly stated to be 25,000 mph (11 km/s)). Simultaneously with that turn, the crew cabin rotates within the RX-M's hull, around its lateral axis, so the ship's cabin deck is always facing "down", orienting the audience. Though objects are purposely shown to float free to demonstrate a lack of gravity, none of the five crew members float, apparently unaffected by weightlessness.[3]

The RX-M's jettisoned first stage, with its engine still firing, and a later meteoroid storm (inaccurately referred to in dialog as meteorites) both make audible roaring sounds in the soundless vacuum of space that can be heard inside the crew compartment. The clusters of those fast moving meteoroids appear identical in shape and detail (actually, the same prop meteoroids were shot from different angles and positions, then optically printed in tandem, at different sizes, on the film's master negative).[3]

A point is made in dialog that the RX-M is carrying more than "double" the amount of rocket fuel and oxygen needed to make a successful round trip and landing on the Moon; while impractical for various reasons, this detail becomes a convenient, then necessary plot device in making the later Mars story line more believable.[3]

Several scenes in Rocketship X-M involving the interaction between the RX-M's sole female crew member, scientist Dr. Lisa Van Horn, her male crew, the launch site staff, and the press corps provide cultural insights into early 1950s sexist attitudes toward women. One notable scene involves Van Horn and expedition leader (and fellow scientist) Dr. Karl Eckstrom rushing to recalculate fuel mixtures after their initial propulsion problems. When they come up with different figures, expedition leader Eckstrom insists they must proceed using his numbers. Van Horn objects to this arbitrary decision, but submits, and Eckstrom forgives her for "momentarily being a woman". Subsequent events prove Eckstrom's "arbitrary decision" to be wrong, placing them all in jeopardy.[3]

Lippert's feature was the first film drama to explore the dangers of nuclear warfare and atomic radiation through the lens of science fiction; these became recurrent themes in many 1950s science fiction films that followed.[3] Dalton Trumbo, black-listed during the McCarthy era, script doctored the film's Red Planet sequence, adding the horror of an atomic war having occurred on Mars; his name does not appear in the film credits.[5][citation needed]

New footage added

[edit]Rocketship X-M was rushed to market to be in theaters before the more lavishly produced but delayed Destination Moon that was finally released 25 days later. A lack of both time and budget forced RX-M's producers to omit special effects scenes and substitute stock footage of American V-2 rocket launches and flight to complete some sequences that otherwise would have been made using the Rocketship X-M special effects miniature. These V-2 inserts created very noticeable continuity issues.[4]

In the 1970s the rights to Rocketship X-M were acquired by Kansas City film exhibitor, movie theater owner (and later video distributor) Wade Williams, who set about having some of RX-M's special effects scenes reshot in order to improve the film's overall continuity.[4] The VHS tape, LaserDisc, and DVD releases incorporate this re-shot footage. Williams funded the production of new footage to replace the stock V-2 shots and a few missing scenes. All new footage was produced for Wade Williams Productions by Bob Burns III, his wife Kathy Burns, former Disney designer/artist Tom Scherman, Academy Award winner Dennis Muren, Emmy Award nominee Michael Minor, and Academy Award winner Robert Skotak. Costumes were re-made that closely replicated those worn by the film's explorers, and a new, screen accurate Rocketship X-M effects miniature was built.[4]

The new replacement shots consist of the RX-M flying through space; it landing tail first on the Red Planet; a different shot of the crew heading away from the RX-M to explore the stark Martian surface; the surviving explorers quickly returning to their nearby spaceship, and the RX-M later blasting off from Mars into space. These six replacement shots were filmed near Los Angeles in color, then converted to black-and-white and re-tinted where necessary to match the original film footage. (Unlike the DVD release, the earlier LaserdDisc of Rocketship X-M contains extra bonus material documenting the making of the film and the creation of this new footage.) The film's production and the making of these new scenes were also presented in RX-M feature articles in both Starlog magazine and later expanded in the first issue (1979) of Starlog's spin-off magazine CineMagic. Prints of the original theatrical release version of RX-M are still stored in Williams' Kansas City film vaults.[4] They have not been converted to a home video format.

Image's 50th Anniversary DVD release (2000), under license from Williams, is oddly missing two of his re-filmed Mars scenes: Lippert's original matte painting scene, which has tiny matted-in figures leaving an obviously painted RX-M, is retained instead of the Williams' re-shot replacement scene that has the five explorers heading away from a convincing RX-M effects miniature standing on a barren Martian plain. A new bridging scene, set at the end of the Mars sequence, showing the surviving explorers hurriedly returning to the RX-M, is also missing from Image's DVD.

Award nomination

[edit]Retro Hugo Award: Rocketship X-M was nominated in 2001 for the 1951 Retro Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation, being one of the science fiction films eligible during calendar year 1950, exactly 50 years after the film's first release. (50 years, 75 years, or 100 years prior is the eligibility requirement governing the awarding of Retro Hugos.)

Mystery Science Theater 3000

[edit]The film was featured in the second cable season premiere episode of the cult film-lampooning television series Mystery Science Theater 3000. Rocketship X-M stands as an important episode in that show's history, showcasing iconic set redesigns as well as the introduction of Kevin Murphy and Frank Conniff to their long-running performance roles as Tom Servo and TV's Frank, respectively.[6]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b "8 War Pix Among Top 50 Grossers". Variety. 3 January 1951. p. 59.

- ^ a b c Rocketship X-M at IMDb

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Warren 1982.[page needed]

- ^ a b c d e f g Williams, Wade. "Re-making Rocketship X-M". CineMagic magazine #1, 1979.

- ^ "CineSavant Column – CineSavant". cinesavant.com. Retrieved 2019-06-30.

- ^ "'Episode guide: 201- Rocketship X-M'" Satellite News. Retrieved: May 26, 2016.

Bibliography

[edit]- Hanson, Peter. Dalton Trumbo, Hollywood Rebel: A Critical Survey and Filmography. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company. 2015. ISBN 978-1-4766-1041-2.

- Miller, Thomas Kent. Mars in the Movies: A History. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2016. ISBN 978-0-7864-9914-4.

- Parish, James Robert and Michael R. Pitts. The Great Science Fiction Pictures. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1977. ISBN 0-8108-1029-8.

- Strick, Philip. Science Fiction Movies. New York: Octopus Books Limited, 1976. ISBN 0-7064-0470-X.

- Warren, Bill. Keep Watching the Skies: American Science Fiction Films of the Fifties, 21st Century Edition, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2009, First Edition 1982. ISBN 0-89950-032-3.

External links

[edit]- Rocketship X-M at IMDb

- Rocketship X-M at the TCM Movie Database

- Trailer for Rocketship X-M is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive

- Rocketship X-M film trailer on YouTube

- Original soundtrack for Rocketship X-M

Mystery Science Theater 3000

[edit]- 1950 films

- 1950s science fiction films

- American black-and-white films

- American science fiction films

- American space adventure films

- Films about astronauts

- Films about nuclear war and weapons

- Films about extraterrestrial life

- Films directed by Kurt Neumann

- Films set in New Mexico

- Mars in film

- American post-apocalyptic films

- Lippert Pictures films

- 1950s English-language films

- 1950s American films

- Films scored by Ferde Grofé

- English-language science fiction films

- Mystery Science Theater 3000

- Films with screenplays by Dalton Trumbo